-

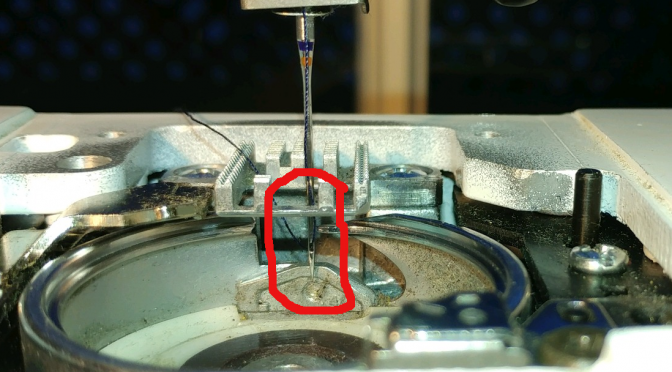

Janome HD 3000 Hook Timing Fix (Won’t Pick Up Bobbin Thread)

My wife was hemming some thick, lined jeans with our Janome HD 3000 when suddenly the bottom thread stopped getting picked up. She re-threaded, changed the needle, to no avail. A few reddit posts later, it became apparent that a likely culprit was the hook timing. I did not know what a hook was a…

-

Bike Tour 2022: Rhône and Mediterranean

In July of 2022 I had the opportunity to bike tour for a couple of weeks. I bought a cheap bike in Lyon and expected to maybe reach Marseille or Montpelllier. But there were quite strong tailwinds down the Rhône and I ended up in Perpignan before I ran out of time. It was overall…

-

Bikes and Hiker-Only Trails

I’m mostly a cyclist. I’d always rather bike than drive, and usually rather bike than walk. But sometimes, I do go for a walk, and this weekend I went for a hike on the Pomo Canyon trail in the Sonoma Coast State park. When I got there and walked past the no-bikes, no-dogs, no-horses sign,…

-

Voting for Bernie Sanders as a Parent

1. Looking Forty Years Forward, and Forty Years Back When I was younger, to the extent that I thought about the future, it was in a detached way. It would be a time where things would be weird and different, but not particularly concerning. I now have a four-year-old daughter and one-year-old son. Having children…

-

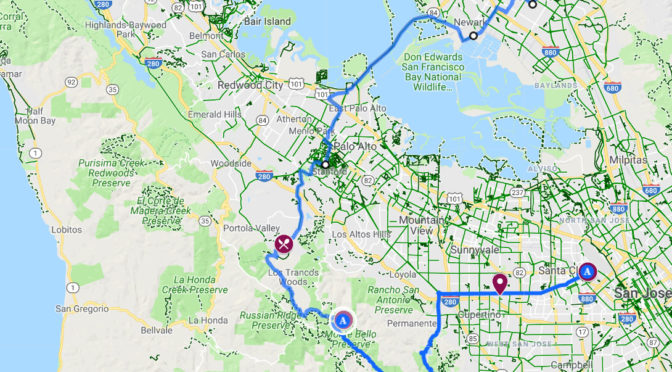

Bike overnight: East Bay to Black Mountain Backpack Camp

Executive Summary and Recommendations This is a 24 hour overnight bike trip, starting and ending in East San Francisco Bay, to Black Mountain Backpack Camp on the peninsula. I took Capital Corridor to Santa Clara on day one (San Jose Diridon would actually be better). There’s not that many trains, so check the schedule (carefully!…

-

The Rorty Reader

This is a review of The Rorty Reader. I came across Rorty when I was doing research on the subject of human rights. After reading four other books on the subject (Nussbaum, Sunstein, Bietz, Morsink) I came across a reference to Rorty’s “Human Rights, Rationality, and Sentimentality” Amnesty Lecture and read it. Overall the experience…

-

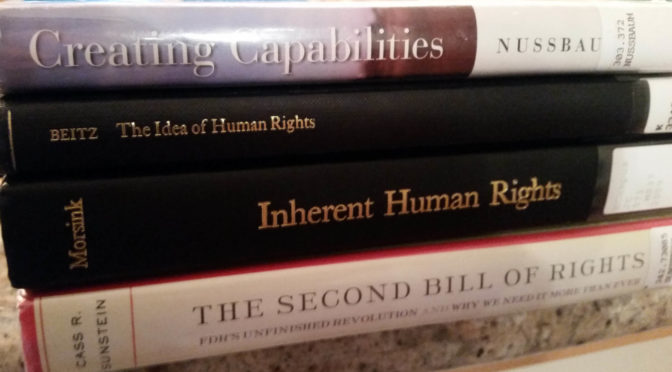

Human Rights Reading: Nussbaum, Sunstein, Morsink, Beitz

A couple of experiences related to human rights recently got me thinking about what the basis is for their existence, and how to think about them as individuals, as political constructs, and his philosophical constructs. I hope to put together an essay that actually makes sense on that topic, but in the meantime here’s my…

-

Smoke Days

At first it was the smell of burning leaves, a very nostalgic smell for me, evocative of Indiana in October, back when I was a kid and you could still burn leaf piles. I had never experienced that smell in California before, in eighteen years of living here. I chalked it up to the weirdness…

-

A four-day mini-bike tour of Marin and Sonoma

I’ve done several longer tours, mostly in Europe. Last weekend the rest of my family went away, so I made the most of it and did a miniature bike tour in Marin and Sonoma, Thursday afternoon to Sunday. This is a map of where I went. SMART rail, the Cal Park Hill Tunnel, and the…

-

Forest, Beach, and River: A Solo Bike Tour of Normandy

[Note: this is a long (but entertaining) story. If you’re just here for the pictures, here’s the gallery , or scroll to the bottom] Preface: April 2017. This trip happened in July and August of 2017, but its story began in April. My wife and I had a one-year old, and had recently decided to have…

-

Bee on a rock rose

Today I learned how bees carry pollen after I took pictures of some in our front yard: it’s that yellow glob on this guy’s rear flank. I also learned (Wikipedia: Honey Bee Defense) that honey bees kill intruding wasps by “balling” them, surrounding them to overheat the wasps and deprive them of oxygen. Stingers are…

-

Map of Normandy Tour

This is a map of my tour that is written up in this post. It may not work with all browsers; it did not render for me on a mobile device (Chrome on Android), so if you’re not seeing anything here, maybe try a different device or browser.